Medicine, Football, and Democracy: The Sócrates Legacy

“I smoke, I drink, and I think" isn't the usual mantra of footballers. When Sócrates proclaimed this, it exposed a streak of obstinacy, a touch of his free-spirited persona, a gift and a curse entwined on the football stage.

“My political victories are more important than any victories as a professional player. A match finishes in ninety minutes, but life goes on.” – Sócrates

Can football truly change society? Is it more than just a game, or even greater than life and death, as Bill Shankly once famously opined? Yes, asserts the revolutionary life of Sócrates. A bohemian in more than one way, Sócrates Brasileiro Sampaio de Souza Vieira de Oliveira was born on 19 February 1954 in Belém, Pará, as the first child of Raimundo and Guiomar Vieira. He became a star of his generation and the years to come, amassing admirers of diverse identities and alignments due to his unique and influential persona.

On the football pitch, the towering figure with curly locks emerged as an agile playmaker and a charismatic leader—an extraordinary blend that granted him the honor of captaining the illustrious Brazilian squad in both the ’82 and ’86 World Cups. Despite his gifts and talents, they couldn’t propel him beyond the quarter-finals of the ’86 World Cup, where Platini’s romantic French squad ousted them.

Nevertheless, his legacy stands shoulder to shoulder with the greats who came before and after him. Aligning with that fact is the Brazil side he led in the Spanish World Cup – a squad that still sparks joy and excitement in the hearts of those who witnessed its brilliance. Evident in the constant citations, it’s often regarded as the finest team that never claimed the championship.

With all that has been said, I share with you a deep admiration for Sócrates. As you delve into this article and discover more about him, you’ll find that he truly stands alone in the vast galaxy of football players. His prominence and influence flourish with each passing day, a testament to the timeless impact of his personality and actions on and off the pitch, drawing admiration from the rarest of competitors.

Like Father, Like Son: The Foundation

Affectionately known as Magrão (Big Skinny) later in his sporting career, Sócrates grew up in a middle-class family, enjoying a life of privilege that stood in stark contrast to the expected rags-to-riches narratives of most Brazilian superstars. A fortune that doesn’t tick the boxes of inherited wealth but rather stems from hard work and resilience can be largely attributed to his father, Raimundo, a self-taught man who defied the odds of being born into poverty, ultimately rising to the rank of a revenue supervisor.

Raised by an erudite father, Sócrates and his siblings were immersed in reading and diligent study from an early age—an opportunity rare among underprivileged Brazilian children of his time. Raimundo, not only an admirer of ancient Greek philosophy but also an avid reader, was resolute in establishing a robust intellectual foundation for his family. This commitment, fueled by the awareness of the hurdles he had overcome, materialized in the creation of a home library and the decision to name his eldest progeny Sócrates.

Thanks to his upbringing, the iconic Brazilian was not just a footballer but also a thinker, philosopher, and medical student even before his much-celebrated footballing legacies came into the limelight. However, that didn’t confine him for too long. Sócrates harbored other passions and interests, one of which, as the world is well aware, is football—a gateway and a medium that reaped multitudes, guided by the man himself.

The Dramatic Entry

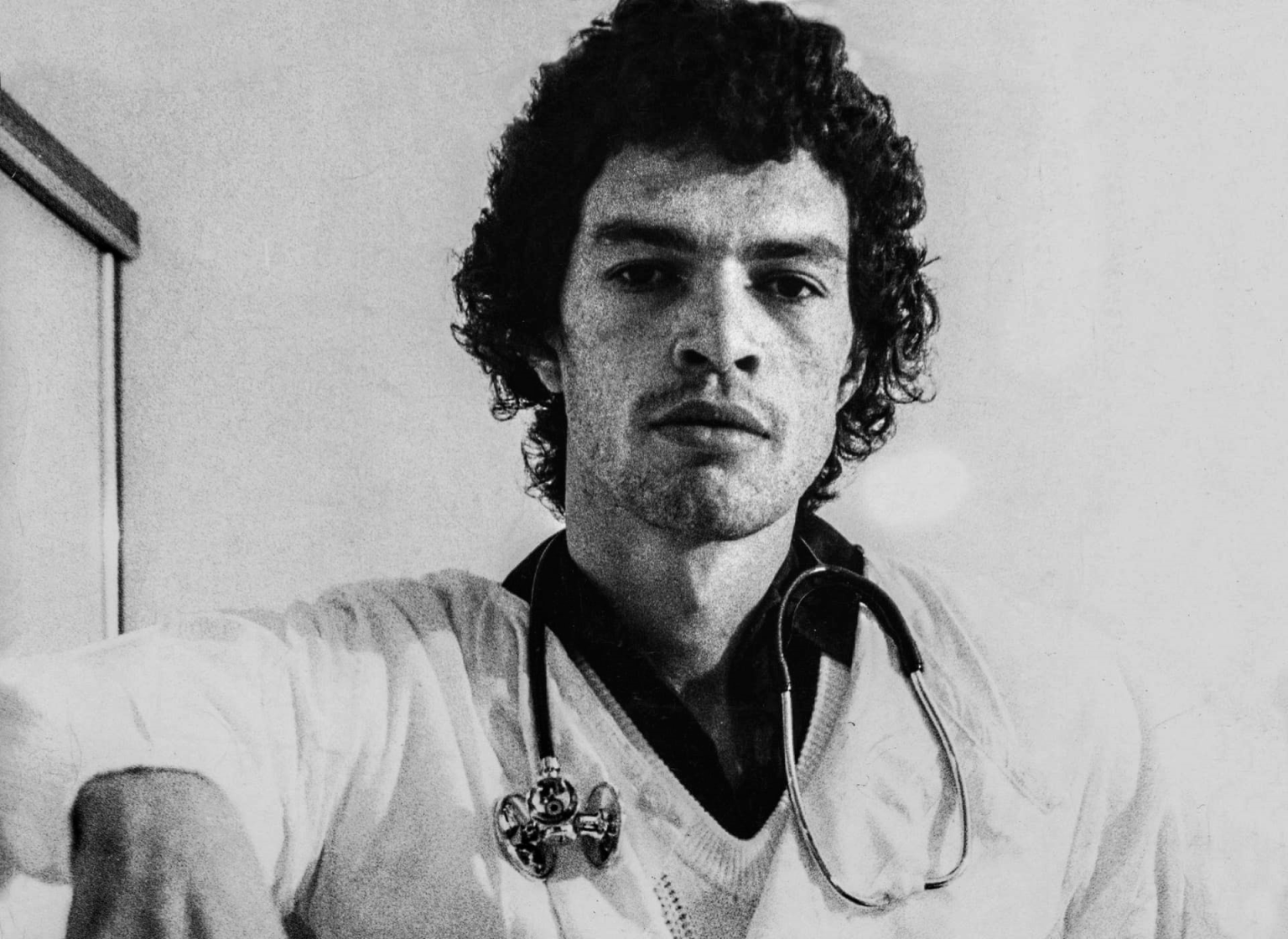

Celebrated for his prowess on the pitch and his iconic back-heel passes, Sócrates didn’t initially find football as a creative outlet. It only served merely as a medium for his primary ambition: studying medicine. In contrast to many teens compelled into lives of hardship, Sócrates, privileged enough to pursue his ambitions, began his medical studies at the Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo.

Amid the academic challenges, football became a welcome respite, unveiling an unexpected journey. His grace and composure on the field, initially a casual diversion, transformed into a dramatic entry into football.

Soon, Botafogo FC, a prominent side from the city of Rio de Janeiro, came knocking on his door at 18. However, all they found was a committed medical student resisting another distraction from his studies. The resistance was strong, but the management was persistent and adamant about not losing an early bloomer. Their efforts proved successful, as the midfielder signed an agreement with one central condition – the privilege of playing for the first team without training, a routine he’d already adopted.

Sócrates seamlessly transitioned into professional football, showcasing versatility as a playmaker. While the management managed his study-focused training prioritization, one persistent habit lingered – a fondness for alcohol and cigarettes. Despite its challenges, Sócrates openly embraced these habits, asserting their role in managing stress and maintaining balance.

“I smoke, I drink, and I think” isn’t the usual mantra of footballers. When Sócrates proclaimed this, it exposed a streak of obstinacy, a touch of his free-spirited persona, a gift and a curse entwined on the football stage.

Sprouts of Revolution

During his time at Botafogo, Sócrates observed a troubling pattern among teammates, marked by subservience, particularly among black players from underprivileged backgrounds. Football served as their sole escape from slums and favelas, where life was marred by crime, violence, and poverty. Descendants of slaves, the most talented, found refuge in the game, but their humble backgrounds were exploited by clubs, leading to non-democratic control over players and staff. Sócrates, a man of learning and bravery, opposed this early on.

Club contracts heavily favored management, giving them complete control over renewals, extensions, and transfers, leaving players with minimal bargaining power. Sócrates, exempt due to his temporary stay, aimed to become a full-time doctor after passing exams.

In 1977, at 23, Sócrates earned his bachelor’s degree, becoming a qualified physician—hence the birth of ‘Doctor Sócrates,’ solidifying his status as a nonconformist. Despite plans to move on, Botafogo offered a salary surpassing what he could earn in medicine. Realizing his medical career was meant to stay, Sócrates signed the contract, leading the provincial team to their first significant achievement within a month. Top Brasileiro league clubs took notice, and Corinthians FC secured his coveted signature, forging an everlasting bond.

Timão: A Special Relationship

Corinthians, lovingly called Timão, sprang from the passion and tenacity of railroad workers, a refreshing contrast to the usual tale of Brazilian clubs molded within the corridors of power and elite influence. In this novel milieu, unpleasant memories from his early years begin to surface. Here, he vividly recalled witnessing his father burning books related to the Bolsheviks and the Soviet Revolution from their library—a desperate measure to evade the persecution of the military junta, who spared no one from their suppression. Rising to power through a notorious coup in 1964, the oppressive regime systematically targeted the working class, intellectuals, and political adversaries alike to quell any pro-democratic resistance.

Reminiscing these horrors once again, Sócrates was convinced to make a change to this status quo in his own way. His commitment to instigate change was unequivocal, encapsulated in his own words:

“Football came by accident. I was more interested in politics. I always had my eyes turned to the social injustices in the country. I just happened to be good at football, which gave me entrance to a very different and privileged environment…If people do not have the power to say things, and then I will say it for them. While I was a footballer, my legs amplified my voice.”

Helping him ace his progressive outlook was the leftist sports journalist Juca Kfouri, whom he befriended in his early years at Corinthians. Moving forward, this camaraderie was soon watered to progression by a couple of changes that took place at the club.

In 1981, a new man was appointed at the club’s helm: the club director of football. The newly installed captain, Addison Alves, turned out to be a sociology graduate, a fellow socialist who had no difficulty in developing a bond with Sócrates. Alongside their teammates, including Zenon, Wladimir, and Casagrande, among others, they propelled the club into a new era, giving rise to a historic movement that would leave an indelible legacy in the annals of football and history at large—the Corinthian Democracy movement.

Democracia Corinthiana

From the onset of his football journey, and notably during his time at Corinthians, Brazilian players faced a strict and oppressive regime of team discipline, mirroring the nature of the military junta. Infamously known as ‘concentração’, under this system, players were required to abstain from going out alone the night before a game and adhere to a curfew of 10 p.m. Players weren’t handed any sway on the decisions inflicted upon them. This was changed. Often in a revolutionary way, like a plot in a movie.

Positing themselves opposite to authoritarianism, Sócrates and his fellow players installed democracy at work. In a swift evolution, the entire club engaged in decision-making processes, granting players the authority to influence every aspect, from dietary choices to whether pre-match meetings should be held and even the players’ passing style. Each footballer had the freedom to stay with the club or depart, adhering to the principles that ‘nobody owns anyone else’ and ‘nobody will be forced to do anything.

The players’ requests and suggestions gained recognition, likely aided by a coaching staff willing to foster open discussions within the team. Such a model of resistance held special significance, transforming Corinthians into a symbol reflecting broader themes in Brazilian society. Beyond openly defying the dictatorship by embracing democratic practices within a prominent sports institution, Sócrates and his teammates demonstrated the effectiveness of rejecting apathy and individualism in favor of collective politics.

Most remarkably, the team achieved notable success under democratic leadership, securing victory in the Campeonato Paulista on two occasions, in 1982 and 1983, throughout the Democracia Corinthiana era.

Taking Matters onto the Pitch: The Headband Tradition

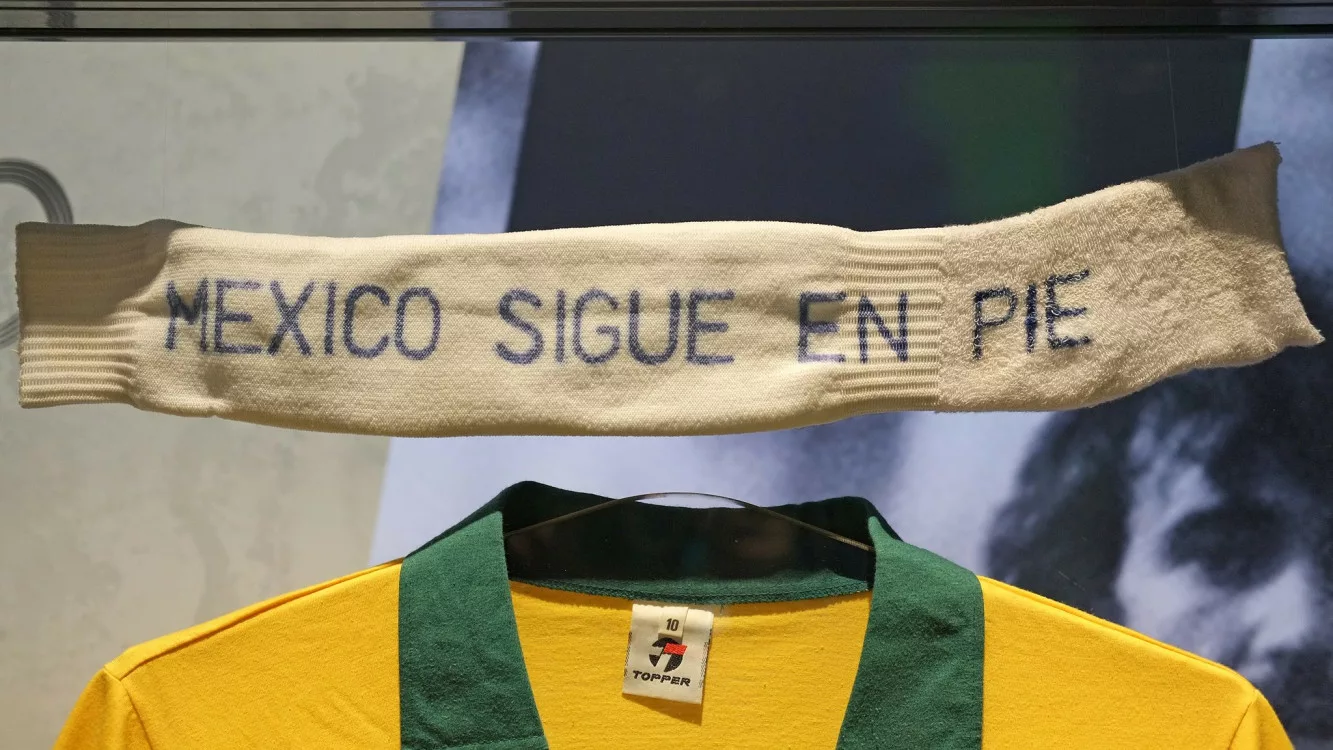

Beyond his distinctive shorts, dark beard, and flowing ringlets, Sócrates was renowned for another unmistakable trademark throughout his career – his iconic headbands.

Adorned with powerful slogans, these headbands first appeared in the 86’ WC in Mexico. Lined up with his teammates for the opening match, Sócrates wore a headband that read ‘México sigue en pie’, meaning Mexico still stands. It conveyed a straightforward yet impactful message to the host nation, still grappling with the aftermath of a devastating earthquake in 1985.

Surprisingly, the headband worn in the first game against Spain was made on the spot using one of the socks from the Brazil squad. Throughout the tournament, the enigmatic midfielder conveyed even more profound political messages, criticizing the American invasion of Libya with slogans like “Need justice,” “No terror,” and “No violence.”

Erudite and articulate, Sócrates understood the impact of a huge stage like the World Cup and how to utilize it to amplify messages beyond the 90 minutes. Although he had exhibited similar acts of bravery before the 86’ WC, the stage and crowd were not as huge.

Wearing shirts inscribed with ‘Dia 15 Vote’ (‘Vote on the 15th’) before Brazil’s inaugural multi-party elections in 1982 and entering the field with a colossal banner proclaiming ‘Ganhar ou Perder, Mas Sempre com Democracia’ (‘Win or Lose, But Always with Democracy’) in 1983 before clinching the Campeonato Paulista—these instances stand testament to Sócrates’ enduring impact.

A man of the people, Sócrates actively participated in the Diretas Já (‘Direct Elections Now’) movement, mobilizing millions and catalyzing the transition to democracy in 1985.

In stark contrast to today’s football landscape, dominated by neoliberal influences that silence and mold players into conformity, particularly in Europe, Sócrates stands out as a beacon. At a time when PR handlers script players, Sócrates rises above as a powerful symbol for a generation manipulated by strings, showcasing the vitality of authenticity and individuality.

As I wrap up this article, Anwar El Ghazi stands dismissed by Mainz for daring to protest against the Palestine genocide through social media. Bayern’s Mazroui, among many, was reportedly silenced in European leagues for the same reason – crying out against inhumanity. Politics is off limits, they said, tightening their yellow and blue bands on wrists and foreheads. Somewhere in heaven, Sócrates may be shedding tears for the Palestinians. May his soul rest in eternal peace.

“There are hundreds of iconic footballers, or brilliant footballers … Most of them, when they retire, are forgotten by all but their most avid fans. Socrate is still remembered and admired by millions of people today in Brazil and the world over, in large part because he took a stand.”- Andrew Downie, biographer of Sócrates.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.